The rise of deep-sea mining as a source of rare minerals and metals may seem like the next logical step for global resource security—but it comes at a hidden cost. According to new research from the University of Exeter, the environmental impact of deep-sea mining is far greater than previously estimated, posing grave threats to marine biodiversity, seafloor stability, and even climate-ocean interactions.

Deep-sea mining vessel operating in open ocean waters. Source: Shutterstock

The Damage Starts Where We Can’t See

Mining operations in the deep ocean—some over 4,000 meters below sea level—disrupt untouched environments that have developed over millions of years. These remote regions, often beyond national jurisdictions, host complex ecosystems of sponges, coral-like organisms, and microbial communities that anchor the deep-sea food web.

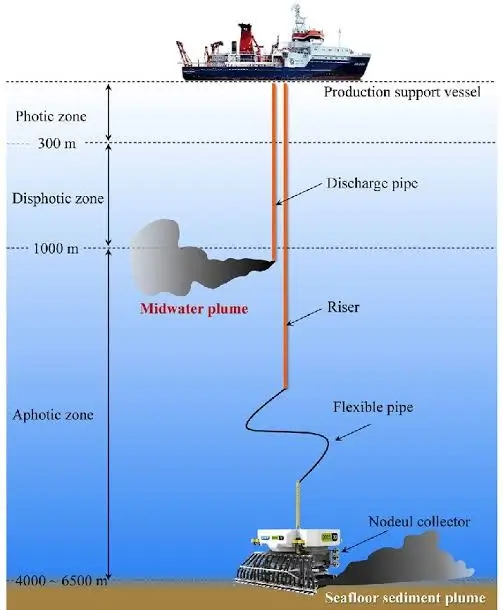

Researchers have identified that sediment plumes created during mining can travel far from the site, smothering habitats and reducing oxygen levels vital to marine life. Beyond the immediate mining zone, fine particles and toxic heavy metals can spread over hundreds of kilometers.

Cross-sectional diagram of mining equipment disturbing deep-sea floor and sediment plumes spreading across benthic habitats. Source: ResearchGate

Key Environmental Risks Identified

A growing number of scientific bodies warn that the push toward large-scale seafloor extraction comes with irreversible consequences. The new Exeter study highlights several specific threats:

- Loss of Biodiversity: Many deep-ocean species are highly localized and slow to recover, making extinction events more likely.

- Habitat Destruction: Nodules, crusts, and hydrothermal vent ecosystems are physically removed or buried.

- Noise & Light Pollution: Artificial disturbance affects navigation, mating, and feeding of deep-sea fauna.

- Carbon Cycle Disruption: Sediment agitation may release stored carbon, with knock-on effects on ocean-climate balance.

- Lack of Oversight: Many mining zones lie in international waters with limited regulatory enforcement.

Side-by-side comparison of undisturbed seafloor vs. post-mining habitat damage (before and after visuals) Source: Nature

The Ethics of Underwater Exploitation

The ethical debate surrounding deep-sea exploitation is gaining urgency. Unlike land-based mining, deep-sea operations occur in fragile ecosystems that few humans have ever seen but that play critical roles in planetary health. Calls for a precautionary pause on such mining activities are increasing.

- Indigenous and coastal communities reliant on ocean ecosystems for cultural and economic reasons are often left out of the conversation.

- Ocean conservation advocates argue that industrialization of the deep sea could outpace science’s ability to understand its consequences.

- Environmental justice experts point out that the ecological footprint of these activities may disproportionately affect regions already vulnerable to climate change.

Also Read: WA vs QLD: Which State Will Dominate Critical Mineral Exports in 2025?

Regulatory Vacuum and Global Calls for Action

While the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued some draft frameworks, clear, enforceable guidelines are still lacking. Several countries—including France, Germany, and New Zealand—have already called for moratoriums or bans until environmental safeguards are fully established.

Deep-sea mining zones and countries supporting moratoriums. Source: Centre for Environmental Rights

Conclusion: The Cost of What Lies Beneath

Driven by the demand for critical minerals and rapid technological advancement, deep-sea mining is pushing into uncharted waters. Yet, the environmental price of extracting these resources could outweigh their material value. As pressure builds to electrify economies and secure rare earths, the mining industry and policymakers must weigh the deep-sea mining environmental impact against irreversible ecosystem degradation.

What happens in the deep ocean may not be visible to the naked eye—but it will be felt for generations. Preserving remote ocean ecosystems, respecting the ethics of underwater mining, and defending marine biodiversity must now become core priorities in the global dialogue around resource development.